It has long been conventional wisdom that young people don’t vote. Compared to older groups of voters, that is true. But it is far less true than it used to be. More than half of 18- to 24-year-olds cast ballots in 2020, a threshold that had not been reached since 18-year-olds were first allowed to vote in 1971. It was a 12 percent increase over that age bracket’s turnout in 2016—one of the largest of any age group.

Of course, 2020 was a presidential year, when turnout generally rises across the board. Is there any reason to think young people will show up for this November’s midterms? Actually, there is. In 2018, turnout among 18- to 29-year-olds jumped to 36 percent from 20 percent four years earlier. That, too, was the largest increase in any age cohort.

Check out the complete 2022 Washington Monthly rankings here.

With Donald Trump now out of office and Joe Biden’s poll numbers in the toilet, you would expect that young people, who overwhelmingly lean left, might lack motivation. And that might turn out to be the case this fall. But a Harvard Kennedy School poll in late April found that “18-to-29-year-olds are on track to match 2018’s record-breaking youth turnout in a midterm election this November.” And that was before the Supreme Court overturned Roe v. Wade.

Although the recent burst of youth voting stems from larger forces—the mobilizing power of social media, progressive backlash to white nationalism—part of the credit goes to the work of student voting organizers, who mobilized young Americans to register and cast ballots despite the pandemic and restrictive voting laws. This includes small, student-led groups that work to get their peers to the polls, as well as national organizations like the ALL IN Campus Democracy Challenge, which helps colleges develop registration and turnout plans.

One of the difficulties these groups traditionally face, however, is getting cooperation from college administrators, who typically don’t consider improving voting turnout systems on their campuses to be part of their jobs (even though the founding mission statements of many of these universities include educating students to be active members of a democracy). All university presidents, though, are concerned about how their schools fare on college rankings. So, to give them an incentive to care about student voting, the Washington Monthly in 2018 began adding measures of student voting to our annual college rankings.

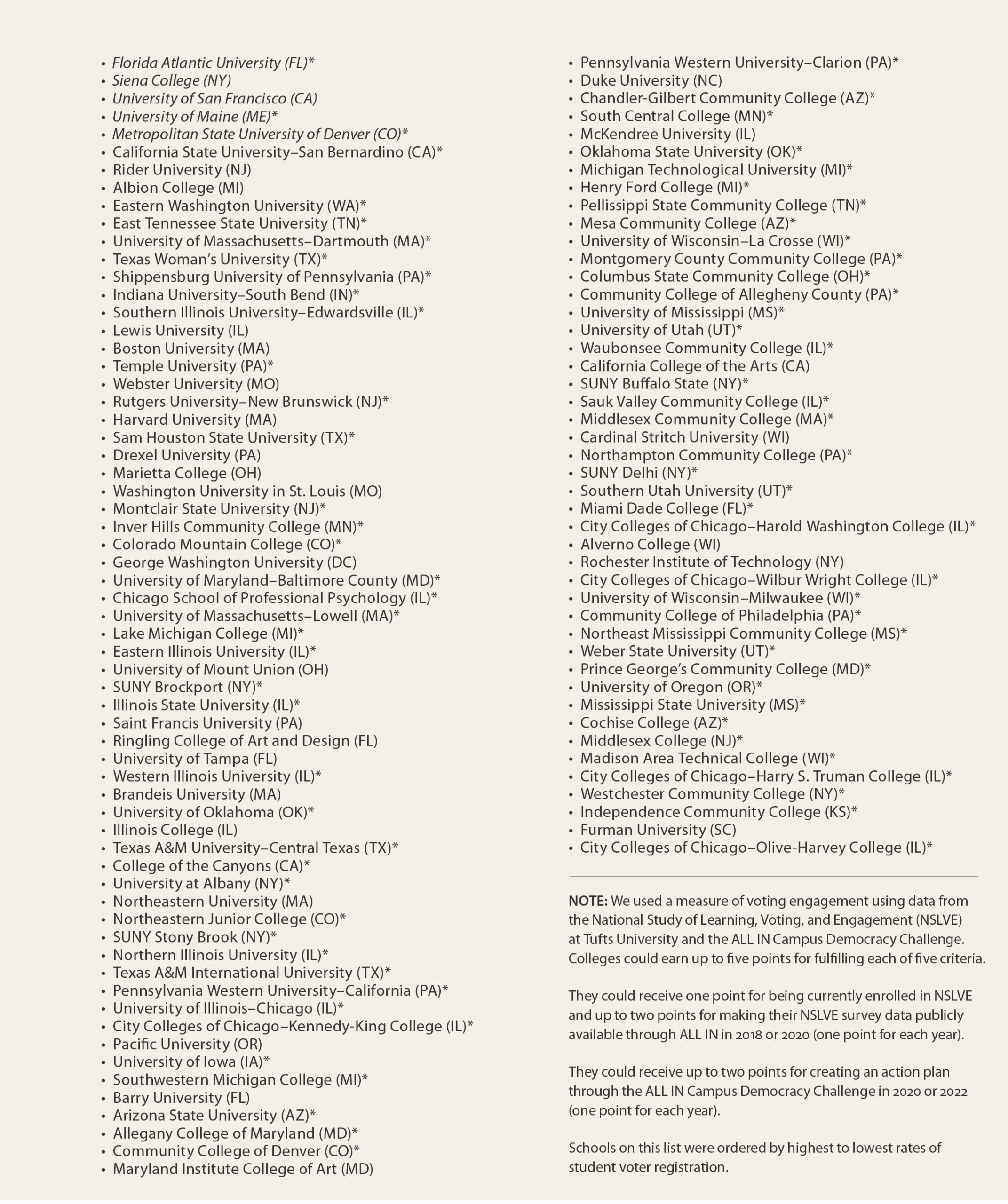

One such measure is a survey by Tufts University researchers that tracks college student voter data: turnout, registration rates. Another way to judge colleges’ civic commitment is through reports that administrators submit about their efforts to promote voter participation. Then, beginning in 2019, we used that data to create an honor roll of colleges that submitted those reports every year and made them available for the public to read.

This year’s honor roll includes some conventionally prestigious schools—Harvard, Princeton—but other U.S. News & World Report heavyweights, such as Columbia University in New York, are missing. Meanwhile, the list is replete with colleges unheralded outside their states and regions, like Weber State University in Utah and the University of Wisconsin–Milwaukee. This kind of diversity is evident throughout the honor roll, with 144 public institutions, 36 community colleges (up from 18 last year), and five historically Black colleges and universities (up from three). If schools like Northern Illinois University (west of Chicago) and Pellissippi State Community College (in Knoxville, Tennessee) can expend the time and energy necessary to make the list, you have to wonder why Stanford, Dartmouth, and Cornell haven’t bothered.

To make the student voting honor roll, universities had to submit 2020 and 2022 action plans to the ALL IN Campus Democracy Challenge. Schools also needed to have signed up to receive data from the National Study of Learning, Voting, and Engagement (NSLVE), which calculates college-specific registration and voting rates. And they must have made their 2018 and 2020 NSLVE data available to the public. In short, schools need to have shown a repeated commitment to increasing student voting—and have been transparent about the results. We then ordered the list by student voter registration rate.

Appalachian State University, near the top of the list, illustrates the kind of tactics campuses can deploy to help students cast ballots. As part of its campus voting action plan for 2020 to 2023, the Boone, North Carolina, school delivered a full-court press of voting events: film screenings, debates, a lecture series, in-class presentations, virtual events, and registration booths at college activities fairs. Appalachian State also hired two fellows for its Campus Election Engagement Project and secured grant funding for another election fellow and other get-out-the-vote efforts. As a result, this public school of 18,000 students, with an 80 percent acceptance rate, outperforms all the highly selective Ivies on the list on voter registration, with a rate of 93.7 percent.

The honor roll saw new heights of student voter registration in 2020, according to data that became available this year. On the list of 230 schools, 127 had a registration rate of 85 percent or more—compared to only 16 such schools on 2021’s honor roll—and 39 were over 90 percent. Participation by universities is higher, too: 25 schools joined the list this year, up from 205 on last year’s honor roll.

Despite these promising results, there’s more progress to be made. This year’s honor roll recognized 230 schools out of a total 850 that received consideration, which means that three-quarters of institutions need to do more to promote civic leadership on campus. Early indicators like that Kennedy School survey from April suggest that youth turnout may remain strong in 2022, but they also warn that young people can’t be taken for granted. In that poll, likely young voters expressed increased agreement with the statements “Political involvement rarely has tangible results” (36 percent), “[Their vote] doesn’t make a difference” (42 percent), and “Politics today are no longer able to meet the challenges our country is facing” (56 percent). When it comes time to push through those attitudes and get those voters to the polls, colleges are on the front line.